The talk made me think of a paragraph that ended up on the "cutting room floor" of an article I've recently submitted to a journal. The paragraph was about the ways that dress in Hong Kong kung fu films, in the late 60s and early 70s, increasingly moved away from the flowing, aristocratic robes of the earlier wuxia films towards the peasant "black pyjamas" of Bruce Lee. Vijay Prashad has suggested in his fascinating book Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting, that in the context of the anti-colonial unrest of the era, Lee's outfit was powerfully loaded in terms of class and anti-colonial identity – for Prashad (who was himself at the time of the release of Lee's films a teenager starting to become involved in an Indian Marxism profoundly influenced by Maoism), Lee's attire could hardly but remind a viewer of the Vietnamese "army in black pyjamas" that also repeatedly graced the screens of the era with images of Asian underdogs kicking US imperialist butt...

(Bruce Lee in Fist of Fury, 1972 - kicking imperialist butt whilst wearing black pyjamas, the uniform of Asian anti-colonial resistance...)

This is also a kind of an imagining – or at least a re-imagining – of the "fashioning" of early twentieth-century revolt...

A further sartorial figure within this 1970s Hong-Kong attempt to imagine – and re-enact – the style of revolution was, of course, the Zhongshan suit that was worn so stylishly by Bruce Lee in Fist of Fury (1972). Lee's Zhongshan is white, which, of course, in China, is the colour of mourning. This, though, in the context of Lee's character's fury against the murder of his teacher by a foreign occupying power, is a peculiarly politicised, nationalist, anti-colonial kind of mourning.

(Bruce Lee's white Zhongshan in Fist of Fury)

The Zhongshan must have been a profoundly loaded piece of clothing in the early 70s. The Zhongshan suit, in fact, is named after the nationalist revolutionary Sun Yat-sen, whose most popular name amongst Chinese is in fact Sun Zhongshan (zhong means centre, and shan means mountain). The Zhongshan was a suit designed by the nationalist revolutionaries to express their political values immediately after the revolution of 1912. (Sun himself is said to have had a hand in its design.) It was, first and most obviously, a rejection of the Manchurian styles of dress of the Qing Dynasty, which had been used very much as a form of social control. The style of the Zhongshan seemed to borrow much from the Western suit, but clearly gave it an oriental twist, both making a claim for modernity, but also marking a difference to the hated Western powers which had beset China over the preceding centuries. In fact, the suit made a clear reference to contemporary Japanese military cadet uniforms, which Sun would have seen during the years of his exile there, with Japan also serving as the model of a successfully modernising East Asian nation. (I can hardly but make a nod here to Jane Tynan's discussion this evening of the militarisation which must have pervaded Irish society at exactly this point in time, with the development of the militias who she discussed in her talk, and who went on to take part in the 1916 uprising. The zhongshan was also a means to bring a military iconography into the everyday.)

The Zhongshan, however, is better known in the West now as the "Mao suit" – the Chinese communists took up the style during their alliance with Sun Yat-sen's nationalist party, and the fashion stuck with them. One wonders quite how Bruce Lee's (super-sylish, minimal and perfectly tailored) Zhongshan would have been read at what was still the height of the Cultural Revolution, where the Maoist Zhongshan (rather less fashionable though this version may have been!) was very much the uniform of the day for mainland males, made to symbolise the unity of the Chinese proletariat. In the wake, still, of the 1967 disturbances, and in the shadow of a continuing student movement, how would this clothing have made sense in Hong Kong in 1972?

(Both Mao and Chang Kai Shek are pictured here wearing the Zhongshan.)

Interestingly, director Chang Cheh (discussed elsewhere on this blog, with regards to the ways that his work was intertwined with the 1967 Hong Kong riots, and the ways his films are haunted by this radical moment) has claimed that Lee took these suits from his own prior film, Vengeance! (1970). Indeed, in this, David Chiang also wears both black and white suits that Lee's own are very close to in style, and Chiang even perhaps outdoes Lee in looking dapper and stylish, the white Zhongshan, in Vengeance!, serving as a canvas for Chang's signature motif of a drenching in lurid red blood, the glamour of the garment gaining from Chang's tragic heroism.

(David Chiang's black Zhongshan in Vengeance!, 1970)

It's interesting that when Chang discusses the suit he (or at the very least his translator) calls it a "white student uniform (or Zhongshan suit)" [The Making of Martial Arts Films, p.22] - making a connection to student movements. In this regard (and in particular in the light of Chang's attempt earlier in the same essay to link his films to the student movements of the 60s), Vengeance! starts to become legible as a kind of a political allegory, with David Chiang's youthful hero figuring as a terrible force of retribution. His individual struggle against the corrupt system of power, wealth and authority that has murdered his brother and attempted to cover up the crime starts to signify a larger failure of established hierarchies, and a youthful, iconoclastic revolt against these.

(When David Chiang wears white, you know things are about to turn sour for all involved...)

(David, you'll never get the stains out of that!)

(Is anyone going to be left alive at the end of this film???)

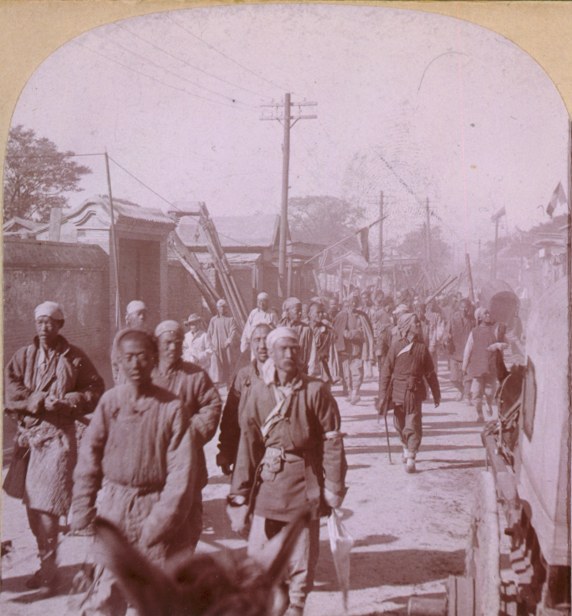

Of course, Jane's talk sent me back to look at other images I've come across – the old photos of the "Boxers" of the Yihetuan (Righteous Harmony Society) that shocked the West at the very start of the twentieth century.

(images of the Boxer Rebellion, from Wikipedia)

Or the attempts in kung fu cinema to imagine the anti-Qing "Shaolin" rebels in the Shaolin cycle.

(lay students survive the burning of the Shaolin Temple, and prepare to spread out to start anti-Qing rebellion across China in Chang Cheh's Shaolin Temple, 1976.)

How do such films attempt to (re)imagine a past of revolution through costume, and how does this relate to the actual attempts of past radicals to figure themselves through dress? There could be a whole research project here...